Psycho: Review

- Carrie Specht

- Apr 22, 2011

- 3 min read

Although the once notoriously titillating shock value of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho has lost its impact over the years, the performances and overall entertainment of the movie have not faded in the least.

Psycho is perhaps Alfred Hitchcock's most recognized movie, and the absolute forerunner to all the many psychopathic killer films to follow. Hitchcock had delved into the subject years earlier with Spellbound, but with psychology playing a healing factor to the disturbed and damaged mind of a capable young man. In the earlier venture, it turned out that the strong and hunky Gregory Peck was suffering from severe shock, and with the love and mothering of Ingrid Bergman is nursed back to health.

With Psycho, Hitchcock uses the mothering factor to represent repression and denial, pushing the smothered child into a world of delicate neurosis. And the beautiful female is not a positive influence, but a degrading one: a common little work girl who has an affair and robs her employers. An instigator of disturbance wherever she goes, she is denied any chance at retribution and deemed deserving of her unfortunate outcome. These are the rules that horror films forever hence do follow.

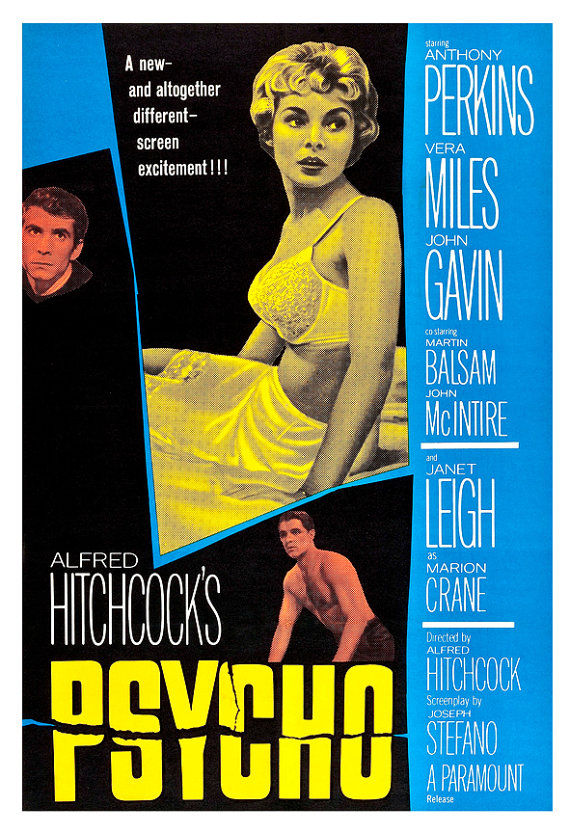

Janet Leigh (mother of Jaime Lee Curtis) plays Hitchcock’s requisite, icy, beautiful blond who finds herself in trouble. Leigh impulsively absconds with the company funds in order to run away with her cash-strapped lover, the square-jawed John Gavin. Before she can meet the dark haired Adonis, the shapely thief is forced to make a pit stop due to bad whether, and encounters a very young and awkward hotel clerk named Norman (Anthony Perkins). Other than peepholes and taxidermy to pass the time, Norman has fostered a close relationship with his demanding mother.

While waiting out the storm, Leigh reconsiders her actions. But before she can do anything about her regrets, she is brutally attacked in the shower in what is probably the most sudden and stunning turn of events in cinematic history (at least until years later when The Crying Game would strongly challenge that distinction). Perkins gives an eerily believable performance as the highly-strung man who desperately cleans up the bloody act he presumes to be performed by his strict and domineering mother.

Unbeknownst to the oddly and immensely appealing neurotic there are many people looking for the missing woman, including her lover, her sister, and a private detective. Inundated with inquisitive visitors, poor Norman becomes more and more muddled, desperate to keep secret the involvement his mother may (or may not) have had in the situation. Ultimately, Norman’s secret and the film’s final twist (now a horror film staple) are revealed to his dire consequence. It’s fair to say that as much as the famed shower scene has become identified as a pinnacle moment in the annals of filmmaking history, the final shot of the film remains just as recognizable as pure a “Hitchcockian” image as any other within the great filmmaker’s career.

The small, but excellent cast includes Martin Balsam (12 Angry Men) as the Detective, and Vera Miles (The Searchers) as the sister. The creative forces at work to create this icon of cinematic history received multiple Academy Award nominations, including Best Supporting Actress for Leigh, Best Director for Hitchcock, Best Cinematography (in Black and White when they still made such a distinction) for John L. Russell, and Best Interior Decoration (also in Black and White and a long past category).